The Story of Santee Normal Training School: A Beacon of Hope in Nebraska

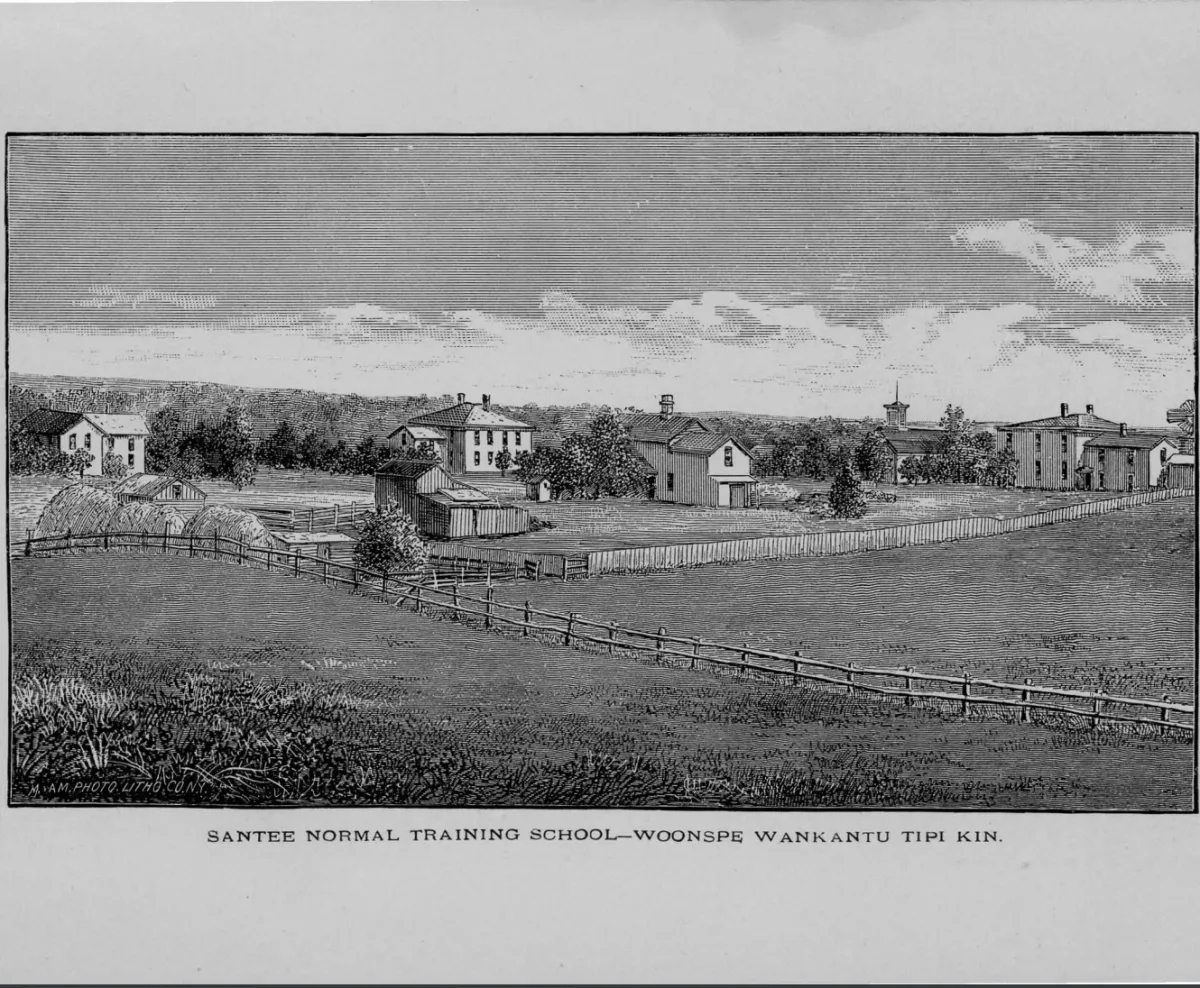

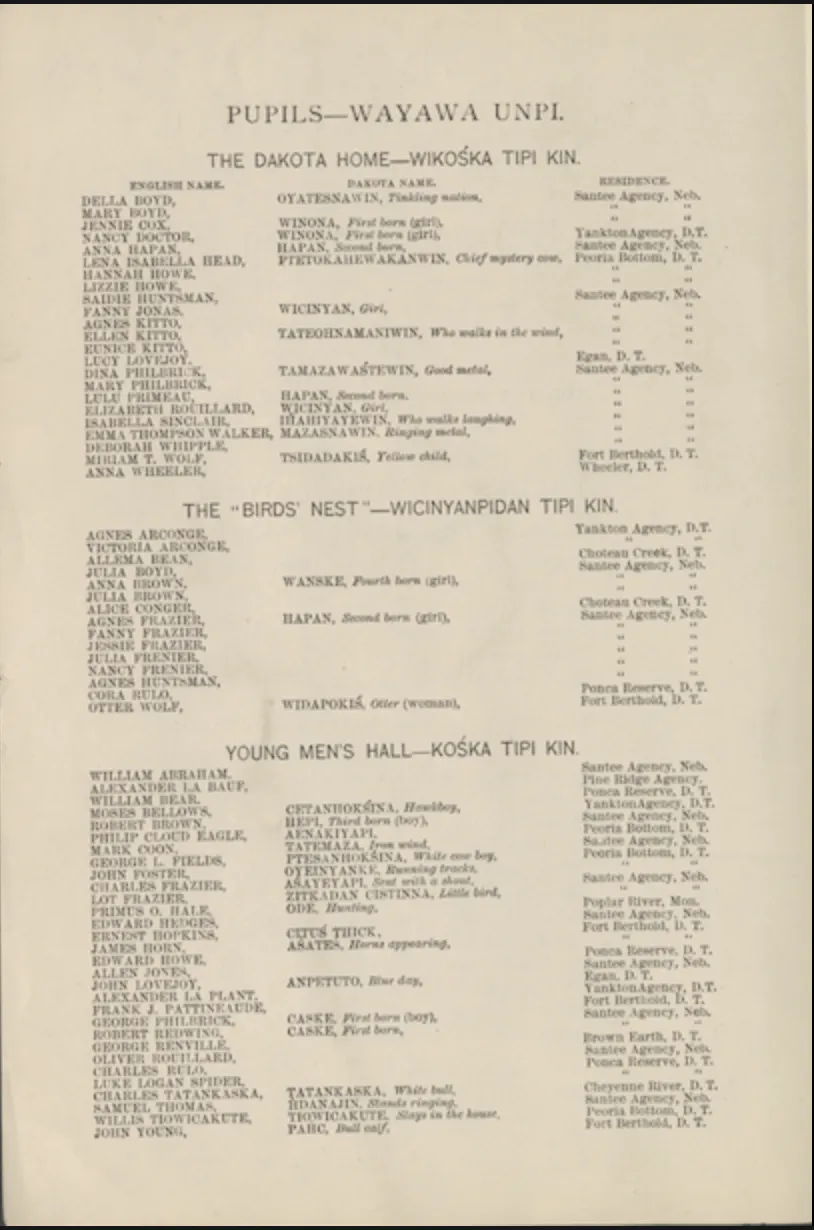

Nestled on the banks of the Niobrara River in northern Knox County, Nebraska, the Santee Normal Training School stands as a poignant symbolof resilience, hope, and the relentless pursuit of knowledge among the Santee Sioux tribe. Founded by the Reverend Alfred L. Riggs in the winter of 1870-1871, this institution was born out of a profound necessity to educate and empower the Santee Sioux, who had been forcibly relocated from their ancestral lands in Minnesota following the Dakota-US conflict of 1862 Reverend Riggs, a Congregational missionary deeply committed to the welfare of the Santee Sioux, envisioned the school as a center of comprehensive education. His mission was to train native teachers who could then propagate education across Sioux communities, ensuring that learning and wisdom flowed from their own ranks. This vision was both radical and revolutionary, as it challenged the prevailing norms of the time, which largely involved imposing external educational standards and practices on Native American communities. The Santee Normal Training School initially opened its doors with 111 enrollments and an average attendance of 69, quickly becoming a vital part of the Santee community. The curriculum was robust, offering courses in history, literature, sciences, mathematics, and the arts, alongside practical vocational training in agriculture, carpentry, and home economics. This blend of academic and practical learning ensured that students not only gained knowledge but also developed skills that were immediately applicable to their daily lives and beneficial to their community. From its inception, the school found itself at the crossroads of cultural preservation and assimilation. One of the fiercest battles was over language. Reverend Riggs passionately defended the use of the Dakota language in education, arguing that true understanding comes from learning in one’s mother tongue. In 1886-1887, the government mandated that only English should be taught, a directive that Riggs contested, emphasizing that “things, not names,” are what matter in education—first understand the concept, then learn the terminology. Despite governmental pressures, the school became a beacon of Sioux advancement and was often described by Riggs as “the high water mark of Indian advance.” However, the strain of balancing governmental demands with the mission’s objectives grew increasingly challenging. In 1893, the government contract was terminated, and the American Missionary Association took over, continuing operations until the 1930s. The legacy of the Santee Normal Training School is a testament to the resilience of the Santee Sioux people. Despite facing numerous challenges, including financial strains and policy changes that often undermined its mission, the school managed to educate thousands of students over its 67 years of operation. By the time it closed in 1937. Today, the story of the Santee Normal Training School serves as a powerful reminder of the importance of education in empowering marginalized communities. It highlights the need for educational systems to respect and incorporate indigenous languages and cultures, rather than seeking to erase them. The school’s commitment to providing a holistic education that respected the cultural heritage of the Santee Sioux while equipping them with the tools to navigate a changing world remains a guiding principle for educators and policymakers today. As we reflect on the legacy of the Santee Normal Training School, we are reminded of the enduring strength of a community that, despite numerous adversities, continued to value knowledge and cultural identity. Their story is not just one of survival but of profound contributions to the broader tapestry of American educational history.